Daniel Libeskind: Exclusive interview on memory and identity, his architectural philosophy and designing a museum for Richard Leakey

Citizens should be empowered to play a much more active role in the design of the built environment as part of democratic society, Daniel Libeskind has argued in an exclusive interview with CLAD.

The architect – known for designing buildings that explore themes of memory and identity – said that the need to enhance public participation in the design process is “the biggest challenge facing architecture today”.

He also discussed his experiences designing a forthcoming evolution museum in Turkana, the acclaimed Jewish Museum in Berlin, the planned Kurdistan Museum in Erbil, and the masterplan for the World Trade Center in New York.

You can read the full feature below.

The new issue of CLADmag – our quarterly magazine – is available to read now online and on digital turning pages.

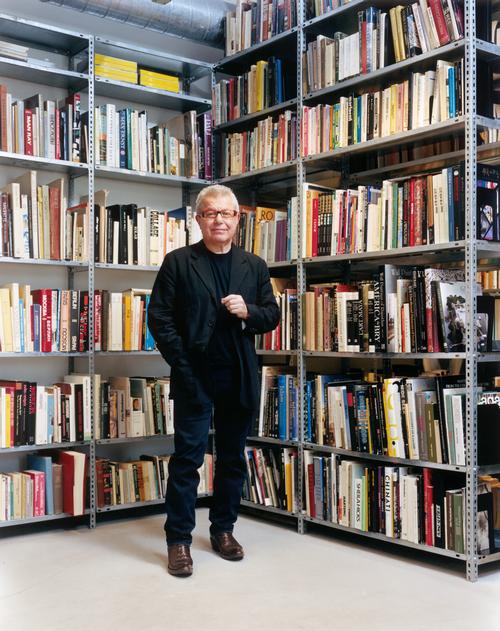

Daniel Libeskind met Kim Megson in London to reflect on some of his career-defining projects, discuss his latest commissions, and share his passion for music

The renowned paleoanthropologist Richard Leakey is planning to build a museum like no other, located on the remote shores of Lake Turkana in northern Kenya.

The site is not far from the spot where, in 1984, Leakey and his team discovered the 1.6 million-year-old Turkana Boy – the oldest and most complete early human skeleton ever found.

Now he wants to establish an attraction dedicated to no less a subject than the origins of our species. To design the museum, Leakey approached an architect who has built his reputation creating cultural institutions and public buildings that convey concepts of identity, memory and belonging.

Articulating history

Daniel Libeskind once summed up his work as “meaningful architecture that articulates history,” and few architects have so openly, and at times confrontationally, used form as he does to explore abstract ideas. His buildings – from the Jewish museums in Berlin and San Francisco to Dresden’s Military History Museum and the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto – welcome visitors into a world of sharp angles, interlocking volumes, fractures and voids.

Studio Libeskind, the New York practice the Polish-American leads alongside his wife, Nina, has over 20 major projects in the pipeline. However, it’s the Leakey museum that is occupying Libeskind’s thoughts when I meet him on a warm afternoon in London. He’s in an animated mood – his wide smile, friendly laugh and rapid-fire delivery a contrast to his trademark all-black outfit – and he’s keen to talk about the Kenya project.

“This is one of the most exciting projects I’ve ever worked on. When I first met Richard to discuss it, there was not a question in my mind that I wanted to be involved. He’s a true visionary and not many architects are lucky enough to work with a genius like him.”

Early design sketches for the museum complex show a footprint that echoes the shape of the African continent. A cluster of buildings, including a chamber of humanity, a planetarium and a dinosaur hall, are shaped to loosely resemble Stone Age tools and are organised around a central hall that rises 15 storeys into the sky. The museum will be built using traditional Kenyan construction methods and materials “to use local genius to create a space worthy of the theme.”

“Until about 8,000 years ago, we were all Africans. This project is about Africa, but it’s also about every human alive, contemplating what accidents of nature and what adventures brought us here, and where we’re going next,” says Libeskind.

“The site is unlike any other place in the world. It’s got a beautiful range of mountains. It’s got the desert. It’s got the lake. There’s no light pollution so you can see all the stars. My idea was to connect the building to that earth and that sky because it is all interconnected in the greater story of humankind.

“Inside, the museum is about time, but it’s also about space. We’ll use materials, proportions and spatial constructs to capture moments of revelation as people pass through the building. It’ll be as if they’re on a pilgrimage exploring the memory of humanity.”

Provoking imagination

For Libeskind, the physical presence of a museum is every bit as important as the exhibits stored inside. A favoured maxim is “a building has to be meaningful and it has to tell a story.”

Perhaps his most famous museum, also his first, is the best example of this. Twelve years passed between Libeskind completing his design for the Jewish Museum in Berlin and the building finally opening in 2001. When it opened, there were no exhibits inside to see, but visitors still flocked in their hundreds of thousands, drawn by the building’s emotive, visceral, divisive design.

Almost 20 years on, the space still has the capacity to shock; its zigzagging plan evokes a broken Star of David divided by “a straight line whose impenetrability becomes the central focus around which exhibitions are organised”. You enter through the city’s former Court of Justice and descend into a network of intersecting, slanting corridors and voids that connect underground with Libeskind’s museum.

“The idea for the design struck me suddenly, like a lightning bolt, the first time I visited the site,” Libeskind remembers. “In the houses and apartments next to this Baroque building, Jewish Germans had once lived. Because they were erased from the history of the city, along with many others – the Romani, political prisoners, the infirm, the sick – I sought to construct the idea that this museum is not just a physical piece of real estate. It’s not just what you see with your eyes now, but what was there before, what is below the ground and the voids that are left behind.

“I needed to explain, through the design, what Berlin once was, what it now is, and what it can be in the future. It’s not some redemptive thing and equally it’s not a finished story. It’s a museum that provokes thought and imagination, and I think that is my function as an architect.”

Memory Foundations

On 11 September, 2001, Libeskind was preparing for the public opening of the Jewish Museum later that day. By 2.30pm Berlin time, he and his team watched in horror with the rest of the world as the Twin Towers fell.

A year later he entered, and won, the high-profile ideas competition to develop the area in Lower Manhattan destroyed by the terrorist attack.

Called Memory Foundations, his masterplan had to achieve a fine balance: to mark the memory of the tragedy while fostering a vibrant working neighbourhood. In the end, half the 16-acre site was dedicated to public space, including the Memorial and the Memorial Museum. High-tech offices were planned to re-connect the historic street-grid, while the streetscape would be revitalised by above-ground retail, a transportation hub and a performing arts centre.

Over the years, the project became contentious, marred by battles and legal challenges between Libeskind and the site’s developer, Larry Silverstein. Silverstein had his own ideas about how the new towers should be built and brought in a star-studded and diverse team of architects to build them. Supporters of Libeskind’s scheme felt he was being pushed out of the process and his concepts lost.

Now though, bridges have evidently been rebuilt and Libeskind is reflective about the results, which he says are very close to his original drawings – crucially retaining his idea for large areas of public space.

“It is fantastic,” he says. “When I moved to New York from Berlin to start the project, Lower Manhattan was empty. People didn’t build, office buildings were being given away for free, people left their belongings and never wanted to come back. Now, almost quarter of a million people have moved there as a result of us creating a public space that has a dignity and interest.”

He admits he often found himself “under huge pressure”, dealing with multiple stakeholders – a carousel of mayors, governors and transport officials – while trying to do justice to the victims of the families who lost their lives in the attacks.

“There were times that were very complex and we were under high scrutiny. Every day we were criticised in the newspapers and every day somebody was photographing the garbage we were throwing out, trying to find a story. You have to have a very thick skin. But I grew up in the Bronx, and people there don’t give up so easily,” Libeskind says.

He describes the process he went through as “writing a large-scale score, and you’re the conductor, with your back to the audience. You need total precision, while also giving interpretive freedom to the musicians. Music and architecture are totally linked in my world.”

Music and architecture

As a youngster, Libeskind was a gifted musician.

“I played the accordion. I was the winner of the America-Israel Cultural Foundation Prize for Music playing that strange instrument. And I played it because my parents were afraid to bring the piano to the courtyard in Poland and draw attention to us, because of the anti-Semitism they faced. It was a dark era. So they bought me the accordion, which is a piano in a suitcase. For the competition, I was the only one – out of hundreds of kids – who had their father carry their instrument because it was too heavy for me.”

Such was his prodigious talent, a 12-year-old Libeskind was advised by the violinist and conductor Isaac Stern that he had exhausted all the possibilities of the accordion and should instead master the piano. Libeskind had his doubts, and soon found a better outlet for his creativity in art and, eventually, architecture.

“I didn’t give up music,” Libeskind says. “I just changed my instrument to architecture.”

Last year, the architect was invited by Frankfurt’s opera house to create “an architectural work without architecture”. Called ‘One Day in Life’, he curated 24 hours of musical performances held across the city, with nearly 200 musicians taking part.

“We reconsecrated spaces that have never had music, like a surgical room in a hospital, the city’s big swimming pool, the stadium, the subway station. We filled them with ancient music, classical music, contemporary music. Thousands took part.

“Most people think you have to build something to be an architect, but architecture is more about bringing people into life than just material into life.”

The Kurdistan Museum

Back in 2009, Nechirvan Barzani, the prime minister of Iraqi Kurdistan – Iraq’s only autonomous region – approached Libeskind through an intermediary and invited him to come up with a design for a 150,000sq ft (14,000sq m) museum. Located in the historic city of Erbil, it would be dedicated to Kurdish culture and prepared to confront the horrors of Saddam Hussein’s genocidal attack on the Kurds in the 1980s.

Libeskind accepted the commission, but due to the political and religious sensitivities surrounding the project, he agreed to keep it secret. For seven years, he was only able to share details with senior members of staff. The silence was finally broken in April last year, and with the recent overthrow of Isis forces in nearby Mosul and the Kurdish people voting in favour of independence in a referendum held in September, hopes have been reignited that the project may one day proceed in an atmosphere of peace and stability.

“It was hard not to tell anyone,” Libeskind says, “because this project is not just a fantasy. We’re discussing it with experts, the clients and local authorities. It’s a very meaningful and hopeful project.”

His design is composed of four irregular sections corresponding to the four countries where most Kurds live – Turkey, Iraq, Iran and Syria – with each section taking inspiration from the respective topographical maps and population densities. The volumes are intersected by a line broken into two angular fragments, representing the past and future of Kurdistan.

“I visited the site several times to interview the people there,” Libeskind says. “It was really a genocide in our time. Saddam Hussein tried to kill all the Kurds. There were deportations, murders. Many of the same stories you hear about the Holocaust happened there too. So we have to tell this story, but we also want to include a new sense of freedom and hope to reflect the reality of the Kurdish people and the Kurdish nation, because there is an ongoing story. All my work – whether it’s the Jewish Museum, Ground Zero or the museum in Kenya – is at heart about the future.”

Democracy and design

As the conversation turns to politics, we inevitably turn to the subject of a certain Donald Trump. Libeskind is one of many high-profile architects to have hit out at the US president for his policies, particularly his attempted travel ban of citizens from several Muslim-majority countries. I ask how he assesses the political situation in America now.

“It’s a throwback to a dark time – building walls, withdrawing from agreements, isolating the country, blaming others,” he says. “But I don’t think people in America really accept it. What it has done is to mobilise many people to be interested in politics and to have a voice. That means I remain optimistic.”

If anything, he says, the political climate has only strengthened his own drive to create public buildings that can be unifying spaces, which allow people to learn about each other and to be more tolerant.

“Consensus and unity are needed to challenge the xenophobia, misogyny and fundamentalism in society. When it comes to the built environment, I think one of the biggest challenges is the lack of public participation in the design process.”

Libeskind adds: “Architecture can only thrive in a democratic environment, and that means through involving people. More than just voting whether they like it or they don’t like it, people should be actively encouraged to engage in conversations about architecture itself. I’m a true believer that given some tools and the right discourse, people are very creative. We see it in art. Why shouldn’t people have that same chance to participate in architecture?”

Nina Libeskind manages all aspects of Studio Libeskind, from financial planning to administration and human resources, as well as public presentations, contract negotiations and communications.

She co-founded the practice with her husband, Daniel Libeskind, in 1989, after he first proposed his design for the Jewish Museum in Berlin.

“Nobody believed such a building could be built and so we left the meeting and stood at this crossroads,” he says.

“I said, ‘I’m going to stay in Berlin, but under one condition: you join me.’

“As she is not an architect, I had to learn how to explain my ideas. And believe me, Nina is a much harsher critic of my work than The New York Times.”

“I’ve been so lucky to have had a collaborator in my wife, who shares my values and has always supported what we’re doing. We’ve been married for 48 years, but we still end almost every night with a home-cooked meal, wine and flowers on the table.”

The National Holocaust Monument in Ottawa, Canada

The Canadian government commissioned this permanent, national symbol that will honour and commemorate the victims of the Holocaust and recognise Canadian survivors. The Monument, which opened on 27 September, is located across from the Canadian War Museum. It is conceived as an experiential environment comprised of six triangular, concrete volumes configured to create the points of a star – a symbol that millions of Jews were forced to wear by the Nazis to identify them.

The Occitanie Tower in Toulouse, France

Set to be the first skyscraper in the city, the 150m-high tower’s curvaceous form is interrupted by a spiral of greenery that rises from street level up to the 40th floor. A Hilton hotel, commercial space for shops and a restaurant with panoramic views of the Pyrenees are among the leisure aspects of the project. Integrated into the overall form of the building, the facade and public platform is conceived as a continuous vertical landscape, inspired by the winding plant-filled waterways of the city’s Canal du Midi.

The Modern Art Center in Vilnius, Lithuania

Dedicated to the exploration of works created from 1960 to the present by Lithuanian artists, this 3,100sq m museum is set to be surrounded by a new public piazza located close to the medieval city of Vilnius. Two volumetric white concrete forms will intertwine to create a structure that flows between inside and outside. The interior courtyard will cut through the entire form and feature a dramatic staircase that leads to a public planted roof and sculpture garden. Completion is slated for 2019.

Tampere Central Deck and Arena in Tampere, Finland

This urban scale development, currently in the design phase, will be built on top of existing railway tracks in the heart of the city. The mixed-use programme will include a multi-purpose ice hockey arena, four office blocks topped by residential towers, a practice field, a wellness centre and a hotel. The arena, which occupies one fifth of the complex, will have the capacity to accommodate 11,000 fans and will feature a shopping arcade, bars and restaurants at deck level.

The Zhang Zhidong and Modern Industrial Museum in Wuhan, China

This museum, dedicated to Zhang Zhidong – a 19th-century leader in government who inspired the movement towards modernisation that established China’s steel industry – is nearing completion. The structure features a steel-clad, curved arc sweeping upwards, suspended by two steel and glass footings that provide space for the entrance lobby.

Team Leader (Harrow School Fitness Club)

Centre Manager (Leisure)

Director of Operations

Fitness Motivator

Recreation Assistant/Lifeguard (NPLQ required)

Membership Manager

Recreation Assistant

Swim Teacher

Swim Teacher

Chief Executive Officer, Mount Batten Centre

Swim Teacher

Swimming Teacher

Swimming Teacher

Company profile

Featured Supplier

Property & Tenders

Company: Knight Frank

Company: Belvoir Castle

Company: AVISON YOUNG

Company: London Borough of Bexley

Company: Forestry England